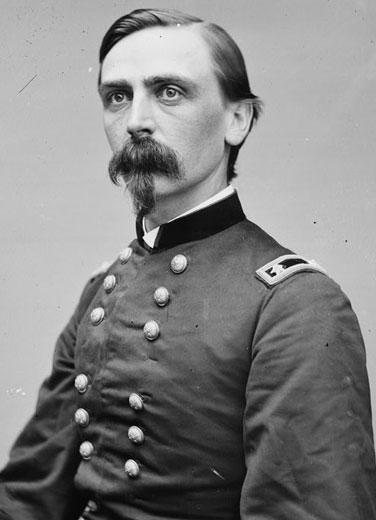

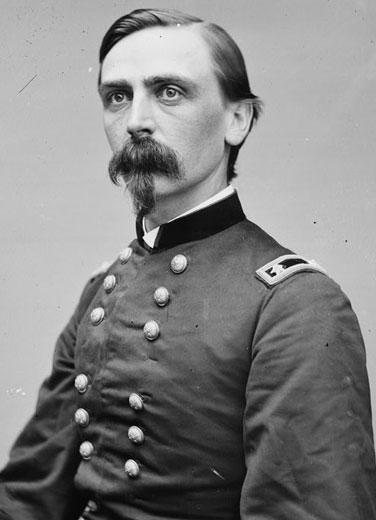

Adelbert Ames Photo: Library of Congress

Adelbert Ames Photo: Library of Congress

Smithsonian magazine has a slideshow of “The Best Facial Hair in the Civil War.” This sort of grooming wouldn’t fly in today’s military, but it makes for interesting viewing.

Adelbert Ames Photo: Library of Congress

Adelbert Ames Photo: Library of Congress

Smithsonian magazine has a slideshow of “The Best Facial Hair in the Civil War.” This sort of grooming wouldn’t fly in today’s military, but it makes for interesting viewing.

Photo: California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

Photo: California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

California prisons are overflowing with inmates, who are packed like sardines into unsafe and unsanitary conditions at nearly double the system’s capacity. Because of the overwhelming volume of people, in one prison an inmate had been dead for several hours before officials realized it. Mother Jones published this piece and accompanying slideshow of the conditions at several prisons in the state, which helped to play a major role in a recent Supreme Court decision to release thousands of inmates.

The photographs in this sideshow provide a glimpse of those extreme conditions: the E-beds (emergency beds) stacked in gyms and dayrooms, the tiny holding cells for mentally ill inmates. All of these photos, some of which were taken by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, were entered as evidence in the California prison case. Three of them (here, here, and here), were appended to the Supreme Court’s majority opinion, suggesting that they had played a role in convincing Kennedy and four other justices to endorse the plan to downsize the state’s prisoner population.

Source: Mother Jones (via Boing Boing)

Photo by lumierefl

Photo by lumierefl

There is a beautiful flowering tree in Los Angeles called the Jacaranda. These trees bloom spectacularly in May all over the city, so Good magazine is calling for readers to submit photos of their favorites. Find out more information here at “Project: Angelenos, Show Us Your Jacaranda Trees.” The resulting photos will be posted on the site’s Picture Show blog.

The Daily Mail has an interesting selection of rare color images from the Library of Congress’ Great Depression collection

If you have three years or so, The Atlantic’s Conor Friedersdorf has compiled an intriguing list of “Nearly 100 Fantastic Pieces of Journalism.” These require more investment than 140 characters, but I think there are a few of us out there who still value long-form journalism.

Friedersdorf calls out usual suspects like The New Yorker, Esquire, Slate and the New York Times, but there are some – like Military History Quarterly – that might not be your regular reading. He also anoints the bloggers of the year, Glenn Greenwald, Julian Sanchez, Radley Balko and Adam Serwer “for their vital work on civil liberties.”

Source: The Atlantic

• Anton Corbijn talks about giving U2 a visual identity, being a freak for accuracy and doing more filmmaking. [BJP]

• RIP Willard S. Boyle, father of the digital camera. [LA Times]

• People are asking if a Seattle cat is a great photographer. (The answer is probably no.) [Huffington Post]

• A fully functional Super 8 movie projector made out of Legos. [Gizmodo]

• How did the guy come up with the idea for the Tumblr site made up of photos of “Pets Who Want to Kill Themselves”? [Salon]

Ashley Gilbertson never set out to be a combat photographer. But he did spend six years in Iraq, mostly for the New York Times, documenting the war and daily life of the country. Then he switched gears, feeling frustrated and disenchanted with war coverage, and wanting a new way to look at war. In his project, “Bedrooms of the Fallen,” Gilbertson photographs the empty, intact rooms of soldiers killed in Iraq and Afghanistan – rooms that are filled with emotion, sorrow and promise. (Last week he won a National Magazine Award for “The Shrine Down the Hall,” an essay published in the Times Magazine.) Here, he talked with us about the project.

How did you first come upon the idea of “Bedrooms of the Fallen”?

It was my wife’s idea. I’d been working a lot on issues about fallen soldiers and about death. We were sitting together one day and she said, “You need to shoot their bedrooms.” And, as usual, she was right.

How do you find the bedrooms?

Searching the Washington Post’s faces of the fallen, local newspapers, White Pages, Facebook. And then it’s just a question of speaking to each family.

Is it difficult to make the initial phone call to the families? What has been the reaction overall?

It changes from day to day. And is it difficult? Of course, but I see it as a minor difficulty. Every time, I just imagine the intense pain and grief that family is going through.

Do you get a sense the families will ever change the bedrooms, or will they be shrines forever?

Again, it changes from family to family. I have a sense some of these rooms will be shrines forever, yes, and I know others have been boxed up.

You were able to get the final funding for the project through Kickstarter. More and more photographers are turning to it, from Tomas can Houtryve to Bruce Gilden. What are your thoughts on it as a new model for funding photojournalism?

I think it’s totally inspiring to work with our audience so directly. I hope it’s something which is sustainable, but we’ll see.

Do any of the bedrooms you’ve photographed belong to soldiers you met or traveled with in Iraq or Afghanistan?

Yes, Kirk Bosselman. I knew him from Falluja.

Why did you choose to do the series in black and white?

So that the viewer had an even playing field to explore the objects in the room. I didn’t want colours to lead you away from things in their bedrooms that might connect with a viewer.

Can one be anything but a pessimist when covering war?

Yes. I always have faith in the human spirit.

You’ve said you had PTSD after working in Iraq. Has that subsided over time, or do you think that will be with you always?

I think PTSD is something you’ll always have, but you learn how to carry.

Is it essential to have colleagues with similar experience that you can talk with?

Yes, it helps a lot, as does seeing a shrink.

Despite the obvious dangers in the job, the recent deaths of Chris Hondros and Tim Hetherington were still very shocking. Do combat photographers feel the risk every day, do they ignore it, how does that work?

If you don’t feel the risk involved, or ignore it, you’re not doing your job properly. One needs to be very aware of everything happening around him at any given time.

Do you ever get burnt out, and how do you deal with that?

Of course I get burnt out. The greatest thing in my life is that I have a wonderful wife and son. I come home to them after an assignment, or a long day, and I can unwind and recharge. And of course, sometimes we take a holiday.

What is your work process like — do you operate on instincts or careful planning?

It’s all a mix of planning and instinct. You need to have done your research about any story you immerse yourself into. I’ll find out who/what/where, etc., before embarking on any trip, but once there, you have to trust your instincts to ensure you find a powerful image.

What is next for you?

More PTSD, suicide and other issues of war on the home front.

Reuters has an interesting blog post from three of its photographers who were on a 15-hour stakeout to get shots of accused sexual predator/IMF head Dominique Strauss-Kahn on Sunday and Monday.

As Mike Segar writes:

The “perp walk”. It’s just what is [sic] sounds like. When the police are ready to transfer an arrested “Perpetrator” they will often “Walk” the person (more like parade the person) escorted by detectives past the press to a waiting car for transfer to the court and corrections systems. Think Law and Order. It’s an old tradition with the NYPD, and there is certain predictability to it. News photographers have all covered them. Nobody likes them. … It’s rarely a chance to make a great or interesting photograph. This is about ‘getting the picture’. Make it sharp; expose it well; don’t miss it! It may well be the only chance to photograph the “perp” before they disappear forever into the court and corrections system. You just don’t know.

It kinda blows our American minds that photographs of suspects in handcuffs are illegal in France. That law, passed in 2000, criminalizes this type of photography until there is a conviction. Here, everyone from Lee Harvey Oswald to Lindsay Lohan have been paraded in front of the cameras — guilty or not.

As New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg told the AP in this article about the famed perp walk: “I think it is humiliating. But, you know, if you don’t want do the perp walk, don’t do the crime.” (Bloomberg did correct himself and say everyone is innocent until proven guilty — but it’s a great quote.)

Brian Blackden is the enthusiastic Concord, NH, freelance photographer who works crime and accident scenes often wearing protective safety gear. We posted on him before, when in November he was arrested for an incident that took place in August, and last week he was found guilty of impersonating an emergency worker.

As The Concord Monitor reports:

Concord District Court Judge Gerard Boyle handed down his verdict at theof Blackden’s trial yesterday afternoon, also finding the photographer guilty of displaying red emergency lights without authorization on the ambulance he brought to the Interstate 93 crash scene Aug. 25. He fined Blackden $1,000 for each of the two crimes and ordered him to pay a $240 penalty assessment but didn’t sentence him to jail time.

Blackden’s attorney, Penny Dean, said he will appeal the impersonating emergency personnel conviction to the Merrimack County Superior Court. Blackden is also suing the state police for allegedly violating his First Amendment rights by seizing his camera at the accident scene.

In related accident-and-crime-scene news, TheDay.com reports that the Connecticut State Senate passed a law that would make it illegal for police officers, paramedics and other first responders to photograph victims at crime and accident scenes and then distribute those photos to others. The bill was in response to a New London police officer who took photos of the victim of a fatal heroin overdose in 2009 and shared them. The bill only applies to photos taken outside the first responder’s job description.