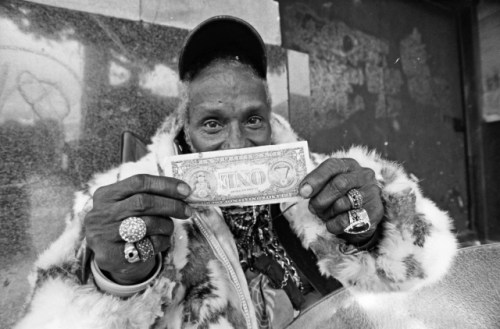

Photo by cinemafia

As street photographers, photojournalists or documentarians, we are under the assumption of, and at times actively identify as being, dispassionate observers. Detached messengers of an uncolored truth. However, the truth is relative, and as human beings the concept of dispassionate observation, while considered an ideal, is an impossible fallacy. We expect to straddle the roles of man and machine, and seem to ignore the idea that one created the other.

The persistence of this myth is tied to the progressive, democratic aversion to a controlled news media. We demand a dissemination of the facts as they are, without agendas, often expecting the breadth and accessibility of the internet to be the causeway that lets that information stream run. We look at bias as a detriment to the story and to prejudice as the corrupter of its information. Is it only because our culture has raised these as buzzwords as evil? We are not only kidding ourselves, we are overlooking the fundamental nature and legacy of humanity.

When a photographer points his lens at a subject and records an image, there is a basic human process taking place. The choice of what matters is a form of prejudice. Not everything has importance, and in fleeting moments it takes instinct to find what is. When that photographer then selects the best representatives from those images to distribute to the public, there is again bias. But, to strive for the cold, clinical characteristics of the presumed un-slanted documentary is to remove this process, and leave a trail of data where intention and feeling once was.

As an example, it recently occurred to me that there is a striking similarity between Ed Ruscha’s seminal work, Every Building on the Sunset Strip, and the popular Google Street View service. Apart from the separation of some 40 years in time, both the execution and result of these two projects would be, to many of an unfamiliar audience, identical. Why then, is Ruscha’s work considered art, while Google’s is merely utility? The answer to this question is simple: intention.

The idea of intention is rooted in the idea of selection, of choice. Ruscha’s work could very well be used as historical documentation, or even as instructional as Google, assuming the urban landscape of Los Angeles was the same as it was in the 1960s. Even Ruscha himself positioned the work as an anthropological document more than a work of art. Still, his choices and his intentions at their heart were human, they carried the interpretation of an experience, rather than the emotionless reconstruction of it.

Photo by cinemafia

It’s a fine line, but as photographers, as journalist, as artists, our personal beliefs and convictions will surface in our work. When we hold something to be of importance, we will show it as so. When we hold contempt for something, it will come through. This is not a bad thing; this is not what we should be avoiding at all costs in the pursuit of infallibility, but instead it is what unifies and enlightens us. If we can come to embrace and promote the power to think and perceive as people and not simply the operators of a camera, we will be respected for doing so and will leave our mark on human history.

Definitely enjoyed looking through your BW work, speaks volumes in itself. keep up the good work!